The following is an excerpt from Pulling Together: A Guide for Teachers and Instructors by Bruce Allan, Amy Perreault, John Chenoweth, Dianne Biin, Sharon Hobenshield, Todd Ormiston, Shirley Anne Hardman, Louise Lacerte, Lucas Wrigh, and Justin Wilson.

Racism remains the theory, while intolerance, prejudice, and discrimination remain its integral practice. Although race is a false category, theories of racial superiority and discrimination continue to circulate, and critical cultural studies are only one of the many ways disciplinary knowledges are unpacking, acknowledging, and hopefully terminating racism.

– Battiste (2013, p. 132)

Colonization was built on racism. Superiority and inferiority were concepts incorporated into Canadian policy, legislation, and practice, where Indigenous peoples were identified as savages and wards of the state. As settlers came and governments were built, Indigenous Peoples’ presence and resistance to assimilation created an “Indian problem” that worked against normalizing a story of Canada as a champion of human rights and a progressive nation. The government’s ongoing need to “fix the problem” continues to have far-reaching effects on identity, belonging, and meaningful participation.

For example, the chief and council system imposed by the Indian Act is based on a Western patriarchal model that disregards traditional forms of governance and community wellness. It is a foreign system that conflicts with the Indigenous place-based value of traditional territory and pits families against families. The system is also largely responsible for the lateral violence or intolerance witnessed in Indigenous communities. The “Crabs in the Bucket”[1] metaphor is one way to describe lateral violence – as resentment and hostility toward self-determination and success.

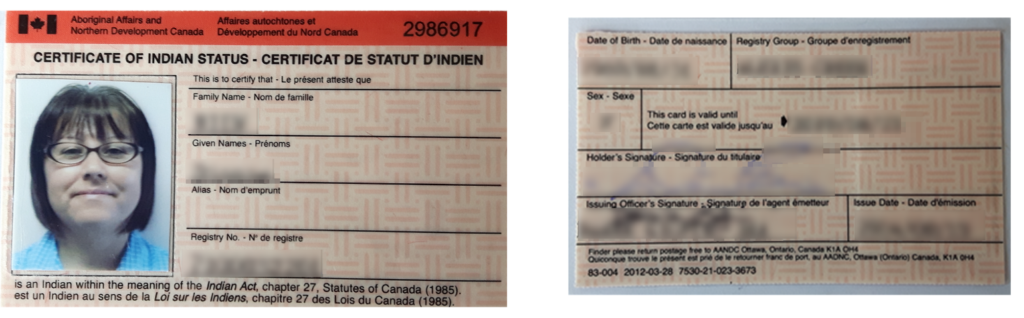

Another example of the disruption of families and communities through racist policy is the Indian Act’s definition of who is a “Status Indian.” Status could be lost by enfranchisement, which included enrolling in and attending university, serving in the military, voting in federal and provincial elections, owning land, and marriage between Indigenous women and non-Indigenous men. These and other forms of enfranchisement applied from 1857 until 1985, when they were finally dropped from the Indian Act. Indigenous women and first-generation children had to prove Indigenous ancestry to regain status. Identity as “status” and “non-status” is still disruptive today and limits access to such things as the ability to live on reserve and to receive health care. “Status” students can seek educational funding support from their registered community, while “non-status” students cannot. Educational attainment data[2] show that women make up the highest percentage of Indigenous graduates (55%) and over half of all Indigenous graduates are “non-status” and live off reserve (Statistics Canada, 2011). There are multiple stories and factors behind these statistics that demonstrate the inequity of the Indian Act.

A Guide for Teachers and Instructors is part of an open professional learning series developed for staff across post-secondary institutions in British Columbia. These guides are intended to support the systemic change occurring across post-secondary institutions through Indigenization, decolonization, and reconciliation.

Learn more:

- Indigenization Guide: Colonization Framework in Canada

- Indigenization Guides

- Actions for reconciliation as citizens and educators

Media Attributions:

- Fig 1.2: Status Identity Card © Dianne Biin is licensed under a CC BY-NC (Attribution NonCommercial) license