The following is an excerpt from Pulling Together: A Guide for Front-Line Staff, Student Services, and Advisors by Ian Cull, Robert L. A. Hancock, Stephanie McKeown, Michelle Pidgeon, and Adrienne Vedan.

While there is great diversity among Indigenous Peoples, there are also some commonalities in Indigenous worldviews and ways of being. Indigenous worldviews see the whole person (physical, emotional, spiritual, and intellectual) as interconnected to land and in relationship to others (family, communities, nations). This is called a holistic or wholistic view, which is an important aspect of supporting Indigenous students. The Canadian Council of Learning produced State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A holistic approach to measuring success [PDF][1] to support diversity of Indigenous knowledges from First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives. Across all three of these perspectives, relationships and connections guide the work of supporting Indigenous students.

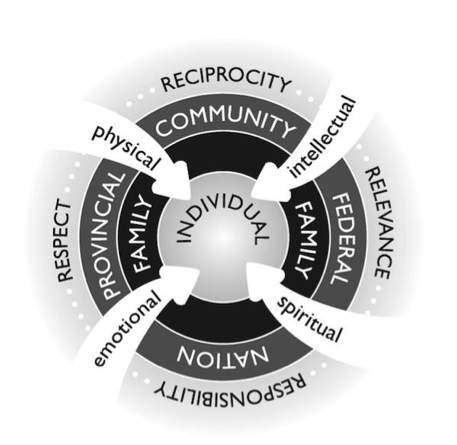

The Indigenous wholistic framework[2] (Figure 2.2 below) illustrates Indigenous values and ways of being and the direct relationship and connection between academic programs and students services in supporting Indigenous students. Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) first provided post-secondary institutions with the 4Rs to supporting Indigenous students: respecting Indigenous knowledge, responsible relationships, reciprocity, and relevance. This was further elaborated by Pidgeon with the Indigenous wholistic framework, which is just one of many models that have been used to think about the wholistic student experience, particularly Indigenous student success (Pidgeon, 2012, 2016a). This framework is not meant to be a model that treats all Indigenous Peoples as the same but a model to show how the diversity of Indigenous understandings of place, language, and cultures relates to the individual, faculty, and community, both institutional and Indigenous communities within and outside the institution. An Indigenous learner who is balanced in all realms (physical, intellectual, spiritual, emotional) and empowered in terms of who they are as an Indigenous person has their cultural integrity (Tierney & Jun, 2011) not only valued but honoured as they go through their post-secondary journey.

This Indigenous wholistic framework provides guiding principles to ensure post-secondary institutions become accessible, inclusive, safe, and successful places for Indigenous students as follows:

Respect

- Encompasses an understanding of and practicing community protocols.

- Honours Indigenous knowledges and ways of being.

- Considers in a reflective and non-judgmental way what is being seen and heard.

Responsibility

- Is inclusive of students, the institution, and Indigenous communities; also recognizes one’s own connections to various communities.

- Continually seeks to develop and sustain credible relationships with Indigenous communities. It’s important to be seen in the community as both a supporter and a representative of the institution.

- Means understanding the potential impact of one’s motives and intentions on oneself and the community.

- Honours that the integrity of Indigenous people and Indigenous communities must not be undermined or disrespected when working with Indigenous people.

Relevance

- Ensures that curricula, services, and programs are responsive to the needs identified by Indigenous students and communities.

- Involves Indigenous communities in the designing of academic curriculum and student services across the institution to ensure Indigenous knowledge is valued and that the curriculum have culturally appropriate outcomes and assessments.

- Centres meaningful and sustainable community engagement.

Reciprocity

- Shares knowledge throughout the entire educational process; staff create interdepartmental learning and succession planning between colleagues to ensure practices and knowledge are continued. Shared learning embodies the principle of reciprocity.

- Means Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are both learning in process together. Within an educational setting, this may mean staff to student; student to student, faculty to staff; each of these relationships honours the knowledge and gifts that each person brings to the classroom, workplace, and institution.

- Results in all involved within the institution, including the broader Indigenous communities, gain experience in sharing knowledge in a respectful way.

- Views all participants as students and teachers in the process.

Through this model, front-line staff, advisors, and student services professionals can begin to see the depth and breadth of relationships to support the whole student.

Media Attributions

- Fig 2.2: Indigenous wholistic framework © M. Pidgeon is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A holistic approach to measuring success: http://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/education2/state_of_aboriginal_learning_in_canada-final_report,_ccl,_2009.pdf ↵

- Pidgeon intentionally uses the “w” in holistic for the Indigenous wholistic framework to reference the whole person. Absolon (2009) and Archibald et al. (1995) also intentionally use the term “wholistic.” ↵