In 2021–2022, BCcampus sponsored the Co-designing with Anti-oppressive Action Frameworks for Curriculum and Pedagogy initiative, funded by the BCcampus Decolonization Grant Program. The work was conducted by professors Bonne Zabolotney and Cameron Neat of Emily Carr University of Art + Design.

The following is the second instalment in a series of excerpts from an interview with Bonne and Cameron to help introduce their framework, what the framework is, how it is designed to be used, and the learning that happened for them along the way.

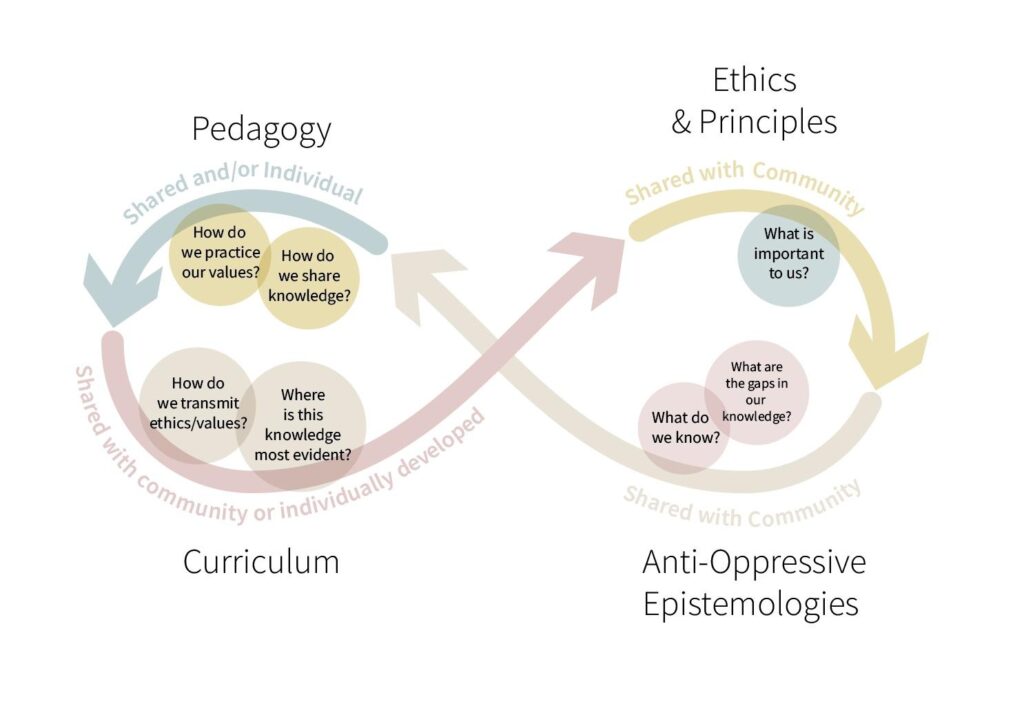

Their Framework: Co-designing with Anti-oppressive Action Frameworks for Curriculum and Pedagogy [PDF]

Listen to Part One of this interview.

Clip 6: What specific things did you do to prepare your faculty participants to do this work?

CAMERON:

One thing that helped is during the summer and fall of 2020 we started having facilitated conversations before we — me and Bonne — started this project, so there was a little bit of groundwork laid, and those were initiated by largely the dean of our faculty. Some of the more difficult initial responses to, for instance, the student petition allowed us to develop a little bit more shared language and shared understanding of how to even have conversations with each other around these issues. That was one thing that helped in the preparation, and actually we ended up with this project bringing that group in for the initial beginning. Okay, we’ve had these conversations now; let’s work on a framework. How do we formalize these in a way that allows us to bring this to the classroom? That was certainly preparatory for that.

BONNE:

Yeah, I think we really lucked out there because at least there was a bit of a willingness to attend because of those initial meetings. There was a bit more of an open mind to new resources then. We had already, prior to starting this project, brought in a couple of different readings, or somebody had said, “Here’s a great book, and here’s some key points.” It kept our colleagues really open to other kinds of resources. Then we could recommend specific resources as primers to start this project. In a way it was a very natural progression. I don’t expect it will always be so natural for other areas. I have to say, the BCcampus open textbook, the Pulling Together guide, is such an excellent primer for this. It’s really great to be able to go to some of these open resources and very public resources. I had also found, just through Googling — I didn’t know this existed prior to our project —the Anti-Oppression Network’s website, which is a Lower Mainland B.C. network. They had a lot of terminologies of oppression. Starting with the kind of vocabulary and the terminologies and understanding the power of our words was really instructive, really important. Of course, we also still had the design-justice resources. We looked at some other partner schools or schools within our Art and Design School Association, and we found the School of Art Institute of Chicago had started to really compile some important resources, almost a little bit too deep as a primer. But it was great to be able to direct people toward those.

Clip 7: What surprising learning or “aha” moments happened for you or your participants?

CAMERON:

I was surprised how quickly some of the shared values came together. I was expecting us to be a little bit further apart. Particularly the five principles in the framework.

Clip 8: Surprises (Cont’d)

BONNE:

The plurality of values allowed us to be more free with our vocabulary to know a lot of different values had the same root, but we could express them in different ways, and we could lead faculty to have that autonomy in expressing those different ways. Pluralism became a surprise when that insight was a pivot point in my understanding of this kind of work, that there really was a difference in how we’re using those words. We also had the process of our outcomes, which was very important. I don’t know if you remember this or not, Cameron, when we were having a post-workshop meeting, Cameron and I were sorting through all the feedback and realizing the relationality, the collaboration, was very apparent but just maybe not in those words and how we synthesized that. Then also making the observation we will always need to learn how to live with our discomfort in these spaces, and that is not always a bad thing. That can be a very productive space. It can be a safe space, discomfort. That was a really lovely moment of those five principles coming together. That’s for me personally also very affirming to have a partner like Cameron, who I trust, and we can be very productive in our conversations. I felt really inspired by working with Cameron and hearing a different point of view and being able to brainstorm with somebody where you just feel so comfortable. I encourage everybody to get a partner in these kinds of projects.

LEVA:

Sounds great.

CAMERON:

And you, too, Bonne.

Clip 9: What Challenges or tricky bits did you encounter along the way? If you could go back in time, what might you do differently?

BONNE:

We did have some challenges for sure. I don’t know there’s ways of avoiding certain challenges. There were sometimes faculty coming to the work unprepared. Sometimes you just have to rely on it. It’s not that Cameron and I have done deep training as facilitators. But design training tends to push you toward facilitation more often than not in practice. There’s a lot of facilitation work you end up doing. I think we’ve really relied on those strengths. We see faculty were not always prepared to have conversations or were surprising each other by bringing certain topics up. We had to really lean into that facilitation work. Sometimes they were very guarded in how they were talking about their work, or they weren’t being specific enough for us to lean into those words. I think if we were to do it differently, I might set up the resources a little bit differently. Rather than say, “Here’s a whole list of resources you should go through in your own time,” I would I might have a look at saying, “If you have five minutes, do this. If you have 15 minutes, do this. If you have an hour, do this.” It would will be easier for faculty to navigate in and out of that preparatory space. It seems like a really basic insight, but one of our colleagues suggested we develop a lexicon as well of use terminology we become comfortable with. You think I would have learned that also from seeing the terminology that came out of the Anti-Oppression Network’s website, but I think using that as a basis as well would have been very helpful for sure.

LEVA:

That’s a good tip. How about you, Cameron? Did you have anything you might want to share about? What would you do differently?

CAMERON:

I’m just in really love. I just learned about Bonne’s thoughts about sharing her course design. I’m thinking, “What a good idea.” Let me think. Some of the major struggles we have were just institutional struggles. They’re hard to know. It’s hard to ask for faculty’s time. It’s very hard when we’re all very stretched for time. With that, I do think sometimes we would run into either a stalling point or a low-energy point that Bonne and I had to come back from and re-focus conversations the next time we got together. So maybe anticipating that a little bit better. Maybe guiding to a smaller conversation point. Because people’s abilities to absorb a resource or their attention span, because they’ve been teaching all day, is less. Maybe having some littler nuggets to just have conversations around more discrete things, I think could have been helpful.

Clip 10: Facilitation, importance of trust and intentional use of asynchronous

BONNE:

That’s also part of trust, letting go, being the authority in the room. Knowing there is some trust, we can allow people — not “allow” — but give space for people to voice concerns, to have opinions. Then they in turn trust us to represent those words if we need to transform them into groupings or say, “This is what we’ve heard.” To reflect back was a really important facilitation technique. They would trust that we were reflecting back to them in that same spirit of trusting and wanting to move to that next step. It is really a big part of that process. One thing I might add to all this is even though we did want to be in the physical room and work, it would’ve been so great for people to have some snacks and a coffee and have that social atmosphere. I think if we could go back or redo it, what I might want to do is really take advantage of that online space and have a few more asynchronous sessions and open it up to a broader group of people. We were being really specific about who we were inviting at some point because we knew people might have more of an interest in contributing, have a little bit more time, be willing to lend us time. But we weren’t opening; we were only keeping it to our Design faculty. I think if we were to have asynchronous sessions, we could probably manage it differently.

LEVA:

Did you do any asynchronous?

BONNE:

Yeah, we did as we were wrapping up and starting to look at pedagogy. We were doing so around midterms, and we just could not find an agreed on time. What we ended up doing was getting the Miro board as structured as we could, being as active as we could, being active participants who were modelling that behaviour. We had a couple of faculty who were very intent on participating, and they also helped provide a bit of leadership and bridging some of the ideas we had and wanted to bring in. I think we had a three-day window where we said, “In the next three days, could you give us a half an hour?” Actually, I didn’t mind that, and it was kind of fun to be able to go on that Miro board, and you see a few pointers moving around, and you knew somebody was in that room, feeling comfortable reviewing the work, and adding a few comments. I’m sorry we hadn’t thought of doing it sooner.

Listen to Part Three of this interview.

About the authors:

Cameron Neat (He/him)

Associate professor of Communication Design

Emily Carr University of Art + Design

Cameron is a communication designer and educator who joined the faculty at Emily Carr in 2016. He holds a BFA in visual communications from Cornish College of the Arts and an MFA in graphic design from the Rhode Island School of Design. His current practices are focused on visual communication and information design for the public health sector as well as community engagement projects aimed at making visible the varied stories of the LGBT+ community.

Dr. Bonne Zabolotney (She/her)

Professor, Faculty of Design and Dynamic Media

Dr. Bonne Zabolotneyis an interdisciplinary designer, educator, and researcher who focuses on Canadian design culture — particularly anonymous and unacknowledged works — and the political economy of design. She holds a PhD in design from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in Australia, an MA in liberal arts from Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, and a BDes from Alberta University of the Arts. She teaches critical studies and communication design at Emily Carr University.

Emily Carr University is situated on traditional unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples — the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh), and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations.

The framework above is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

The featured image for this post (viewable in the BCcampus News section at the bottom of our homepage) is by Francesco Ungaro.