Post by BCcampus Research Fellow Elle Ting, instructional associate at Vancouver Community College’s Centre of Teaching, Learning, and Research.

Background

For those of us involved in teaching and learning during the pandemic, the abrupt shift to emergency remote learning has become known as the pivot. The word choice in our context is itself telling: it evokes images of a graceful tilt in instructional delivery, measured and athletic. In practice, though, the early days of remote instruction were less pivot than panicked uphill scramble, and what quickly became apparent—and not just in the educational sphere—was that COVID-19 was a storm that not everyone was well positioned to weather. Despite the constant refrain that We Are in This Together, emergencies have a way of making systemic failures and the uneven distribution of hardships too obvious to ignore.

Such complexities were front of mind for me and my co-investigators, Andy Sellwood and Andrew Dunn: we work in the Centre for Teaching, Learning, and Research (CTLR) at Vancouver Community College (VCC), and as our college joined the mass migration to remote learning just over a year ago, we started to see common themes emerge and intersect in the inquiries that CTLR was receiving and throughout other institution-wide “pandemic-proofing” initiatives that involved our team. There was a marked increase in reported academic integrity violations; instructors were also feeling frustrated trying to replicate, faithfully, the security of trusted assessments in an online environment. Typically, these grievances were packaged together in implied causation (i.e., that moving assessment online was responsible for a sudden rise in academic misconduct), often enough that we had a working hypothesis practically given to us: Had the conversion of assessments to a remote learning format become the determining factor for increased academic misconduct? If so, and assuming continued remote learning, what means do instructors have to mitigate academic integrity violations?

Unsurprisingly, we also saw a spike in demand among some instructors for third-party digital proctors to protect academic integrity. Across the postsecondary sector, the pivot generated a ready market for quick-fix, “plug and play” options (e.g., Proctorio, Examity) that sell the promise of preserving the integrity of invigilated high-stakes exams with little to no intervention on the part of instructors and institutions. These tools are convenient, but there is mounting evidence that they are ineffective in protecting academic integrity and can potentially introduce new difficulties by exacerbating existing educational barriers for many students, eroding student privacy and encouraging an “arms race” by provoking learners at risk of academic dishonesty to escalate their efforts. Because the incurious use of third-party proctoring ignores academic misconduct as a symptom of high-stakes testing protocols, it replicates and often amplifies the systemic dysfunction baked into the assessments themselves. For all these reasons, third-party proctoring technologies were reasoned to be a poor fit for VCC, whose history and culture are rooted in access and whose students include those with multiple barriers. An institutional decision was made early not to pursue these.

So we knew fairly soon what we could not use and why, but the question of practical significance was whether the options we did have at our disposal had the desired effect of upholding academic integrity. To gauge the effectiveness of the technical and pedagogical measures we had or could readily develop to protect academic integrity, particularly around built-in Moodle functionality and open education practices, we consulted VCC instructors about their experiences with them before and after the pivot. Our project focuses on the following two questions:

- In real terms, what makes the deployment of an alternative assessment tool/method “successful” versus “unsuccessful” for instructors and students, and what educational technology supports can help facilitate effective deployment?

- What can we learn from instructors’ experiences during the 2020 pivot to emergency remote education that we can apply at VCC (and other small to midsize postsecondary institutions) to make the most of online features/formats and alternative assessments in a way that protects academic integrity and supports authentic learning moving forward?

Methods

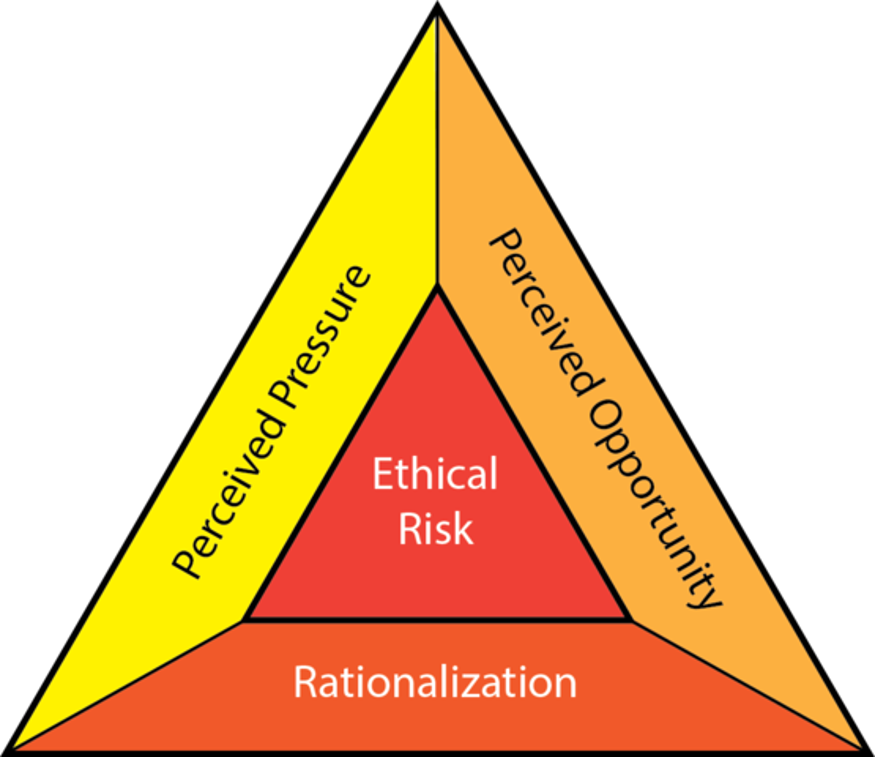

The theoretical framework for our study came from, of all places, research conducted in 1950 by criminologist Donald Cressey on occupational fraud. Cressey’s Fraud Triangle model describes the three risk factors for fraud as perceived pressure, perceived opportunity, and rationalization. The presence of all three factors creates a heightened ethical risk, and an increase in any one of the pressures correlates with a higher risk of committing fraud.

Cressey’s model, as a predictor of fraud risk, has more recently been used to explain and analyze academic integrity violations (Varble, 2014; Feinman, 2018), and we build on this research in applying the Fraud Triangle paradigm to our interpretation of data collected from VCC instructors.

We collected data in two stages: the first of these was an instructor survey Andy and I deployed in November and December 2020 with our institutional research (IR) colleagues Shaun Wong and Alexandra Cai. The survey included questions about assessment formats, student concerns about changes to assessment, student accommodations, and instructor impressions regarding academic integrity. These were framed as a comparative analysis between pre-pivot and post-pivot contexts, and the respondents were limited to VCC instructors who had taught in the winter 2020 (January–April) semester. Of the 939 instructors invited from across the college to participate, 146 completed the survey (15.5 percent); while all respondents were deidentified, IR was able to confirm that the participant sample was a reasonable cross-section of VCC instructors.

The second phase of data collection involved three focus groups in February 2021 that were facilitated by Shaun and Alexandra from IR. Of the 40 instructors who initially agreed to participate, only eight were able to attend the focus groups (~20 per cent). The questions posed at the focus groups asked instructors for their opinions on alternative assessments and their effectiveness at managing academic integrity. Again, IR confirmed that different programs and areas were adequately represented despite the small sample size.

Results

Our analysis of the survey and focus group responses revealed a few surprises. First, we saw a slight overall increase in the use of entirely or mostly multiple-choice-question tests (+4 to 5 per cent) and a net decrease in mostly long-answer assignments (-9 per cent), entirely long-answer assignments (-3 per cent), and essays (-2 per cent); because assessments that feature higher-order questions are generally better for protecting academic integrity, we had expected their use to increase.

Instructors also reported using fewer take-home assignments overall, which challenged our assumption that these, too, would increase. Given that in-person assessment dropped precipitously following campus closures (-33 per cent), it seemed reasonable to expect that instructors would give proportionately more take-home assignments for students to take home, but this was not the case, at least not early in the pivot cycle.

These outcomes become less strange when read against instructors’ perceptions regarding academic integrity before and after the pivot. Prior to the pivot, instructors felt that the risk of academic misconduct was significantly higher in take-home assignments (40 per cent) than in quizzes, tests, and exams (23 per cent); furthermore, for 71 per cent of the respondents, the pre-pivot level of concern regarding academic integrity was “neutral” or “not significant” when it came to quizzes, tests, and exams, whereas only 48 per cent of instructors indicated this low level of concern for take-home assignment. These numbers point to a low baseline confidence in take-home assignments before the pivot occurred.

Instructors’ impressions of their ability to protect academic integrity online post-pivot similarly reflect a lower level of perceived security for take-home assignments and a higher level of trust in quizzes, tests, and exams as reliable measures of student achievement. Although 33 per cent of instructors noted that they became more concerned about protecting academic integrity in take-home assignments post-pivot, the majority (54 per cent) reported that their level of concern about this format was neutral. Meanwhile, 54 per cent of instructors indicated they were more concerned after the pivot about academic misconduct happening during quizzes, tests, and exams. In other words, instructors’ low confidence in take-home assignments eroded further post-pivot, but the integrity of quizzes, tests, and exams was identified as a much greater concern to respondents, since these formats were previously regarded as more secure and accurate.

When asked about strategies they were using to improve the security of quizzes, tests, and exams, instructors were knowledgeable about appropriate Moodle tools that could support this work. The most popular feature by far was the time limit, which 85 percent of respondents implemented; this option also scored highest among instructors in perceived effectiveness (68 per cent). Instructors also described successful adoption of question randomization (62 per cent use; 44 per cent effectiveness), Zoom invigilation (62 per cent use; 45 per cent effectiveness), and academic integrity reminders (72 per cent use; 45 per cent effectiveness). However, respondents acknowledged that students were very concerned about the time limit feature (65 per cent) and Zoom invigilation (25 per cent). Ss the Fraud Triangle identifies perceived pressure and rationalization as risk indicators, there is a possibility that building in these features could simply be trading off one problem (opportunity for misconduct) for another (stressing students enough that they cheat and feel justified in cheating).

Instructors also reported early and significant wins in their use of alternative assessment strategies, with the most common being open-book assignments and tests, project-based work, and higher-order thinking questions. Eighty-one percent stated that their modifications/alternative assessment strategies had been effective to some degree. Generally, VCC instructors are very confident in exploring alternative assessments and expressed excitement to build and experiment more with these: the primary barrier to wider use of alternative assessments was the lack of time. Proper development and evaluation of alternative assessments require dedicated time and labour that are, understandably, difficult for anyone to marshal during a pandemic.

Conclusions and next steps

Almost 13 months into the COVID-19 pandemic, the pivot has made a circle, and our move to remote learning has graduated beyond the emergency stage to something that can potentially make the kind of education that instructors and students want. Quality online assessments that both secure academic integrity and support authentic, student-centred learning are key not just to pandemic-proofing education but to futureproofing it as well.

Our project, supported by the BCcampus Research Fellowship program, explains more concretely what we at CTLR have been learning inductively over the past year supporting VCC instructors through a high-pressure transition to remote learning. By debriefing instructors about their experiences and examining these alongside other institutional data, we expect to deconstruct many assumptions about academic integrity and about “good-enough” assessment practices more generally. One perception we would like to unpack further as we continue our research is whether deterrence and the elimination of cheating opportunities should be the focus for protecting academic integrity or whether options that are less stressful for students (e.g., academic integrity reminders, higher-order questions, etc.) are equally effective or perhaps more effective in protecting against academic misconduct.

As CTLR encourages authentic assessment, the creation of an alternative [online] assessment toolkit following this study would be an important resource for supporting our community of learners and teachers at VCC. It would also be a useful contribution to the wider research conversation around alternative assessment possibilities for B.C.’s postsecondary community and how they can facilitate student access and success.

Selected References

Alessio, Helaine et al. “Examining the Effect of Proctoring on Online Test Scores.” Online Learning. 21(1). 2017. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1140251.pdf. Accessed 22 June 2020.

Chin, Monica. “Exam Anxiety: How Remote Test-Proctoring is Creeping Students Out.” The Verge. 29 Apr 2020. https://www.theverge.com/2020/4/29/21232777/examity-remote-test-proctoring-online-class-education. Accessed 22 June 2020.

Feinman, Yelena. “Security Mechanisms on Web-Based Exams in Introductory Statistics Community College Courses.” Journal of Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences .12:1 (2018): 153–170. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1345&context=jsbhs. Accessed 22 June 2020.

Grajek, Susan. “EDUCAUSE COVID-19 QuickPoll Results: Grading and Proctoring.” Educause Review. 10 Apr 2020. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/4/educause-covid-19-quickpoll-results-grading-and-proctoring. Accessed 19 Apr 2020.

Learn more:

The feature image for this post (viewable in the BCcampus News section at the bottom of our homepage) is by Vlada Karpovich from Pexels